The Rainhill Trials

In 1824 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company was set up by merchants in the area in order to facilitate transport between the two major cities. The idea was heavily influenced by William James a land surveyor and property investor who had the vision of a national railway network after seeing the development of independent colliery lines and the advancement of locomotive technology.

Up until this point railways were generally run using a mixture of cables powered by stationary steam engines and horse haulage, occasionally using steam locomotives for short sections. George Stephenson, engineer for the project advocated using locomotives for the entire line to overcome the issue with cable haulage that one technical issue could paralise the entire system.

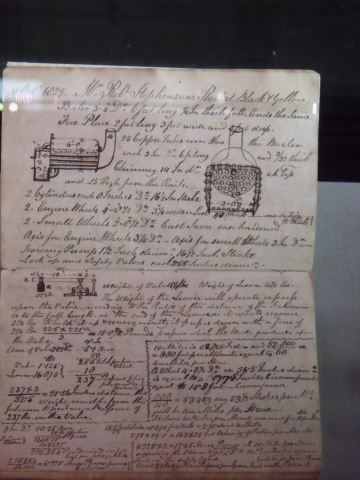

In 1829 as the construction of the line neared completion the directors of the company were still unsure how to power the railway, and so it was decided to hold a competition with a prize of £500, to find a locomotive that could prove the viability of the idea.

Each locomotive was required to haul a load of three times its own weight at a speed of at least 10mph. The trial would take place on the track at Rainhill and each locomotive would be required to travel up the track and return ten times which would come to 35 miles (roughly the distance between Liverpool and Manchester). Due to concern that the rails would break the locomotive would also have to weigh less than six tons including its compliment of water (a machine of lighter weight being preferred in the case of a draw). The price of the engine was to be less than £550.

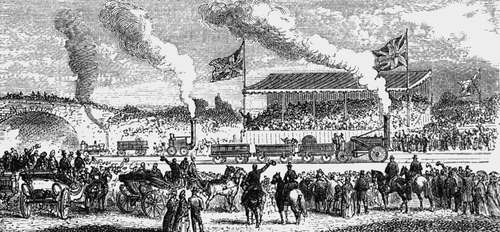

The competition was due to start on the 1st of October 1829, but this was extended in order to give the entrants time to make their machines ready after their journey by ship and waggon to Rainhill. On 6th October 1829 the Rainhill Trials began. Of the ten entrants to the competition only four made it to the trials, Novelty, Perseverence, Rocket and Sans Pareil.

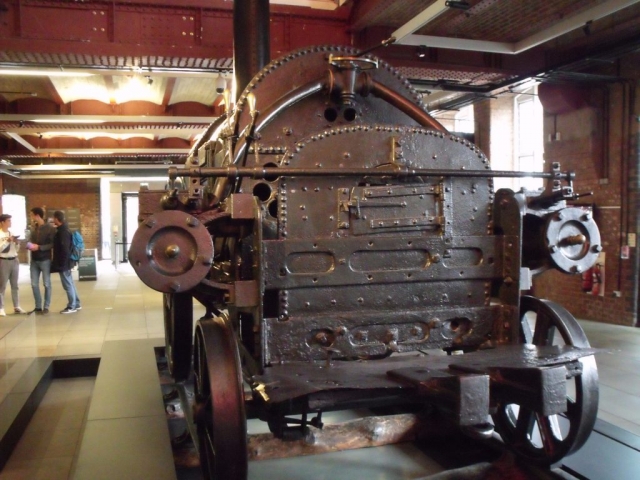

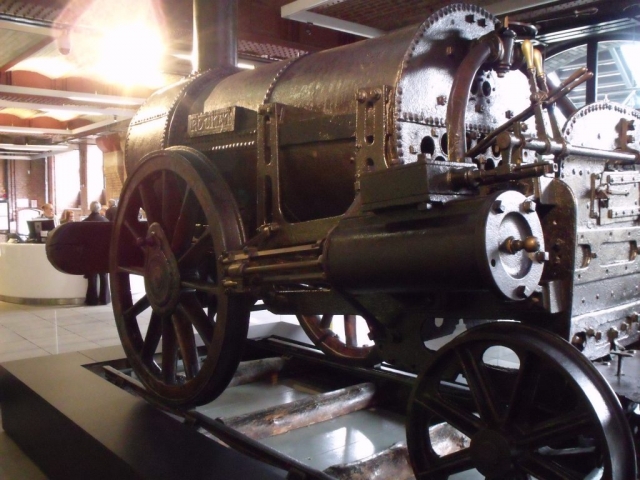

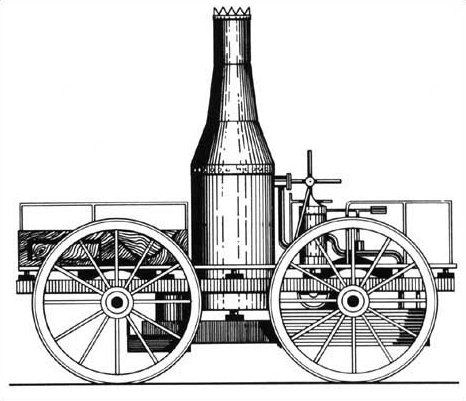

Hackworth’s Sans Pareil

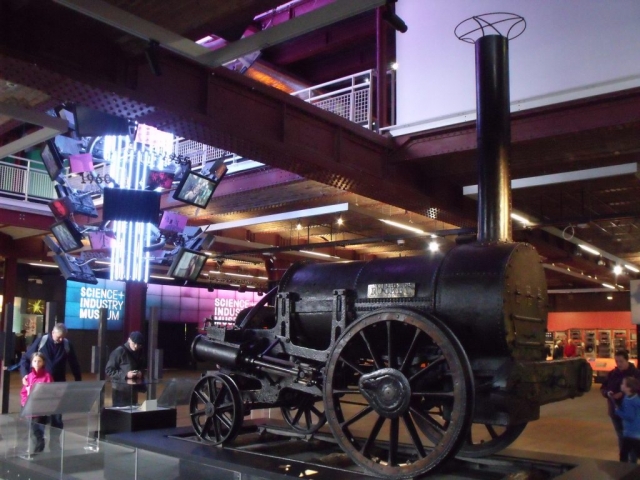

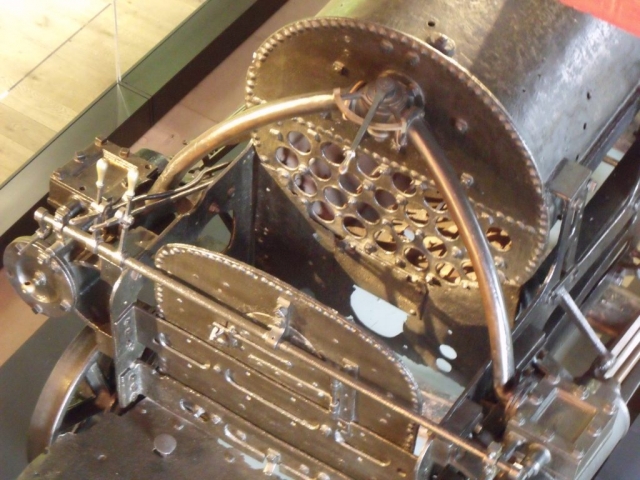

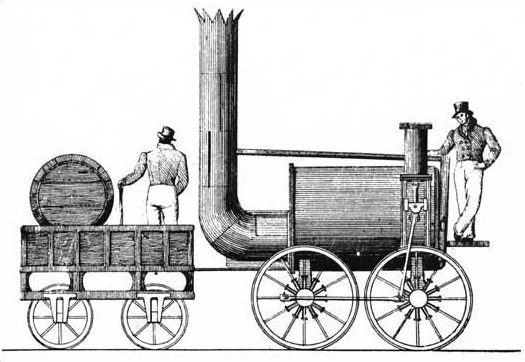

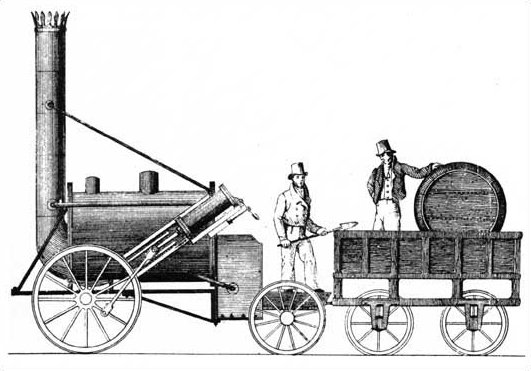

Stephenson’s Rocket

Burstall’s Perseverence

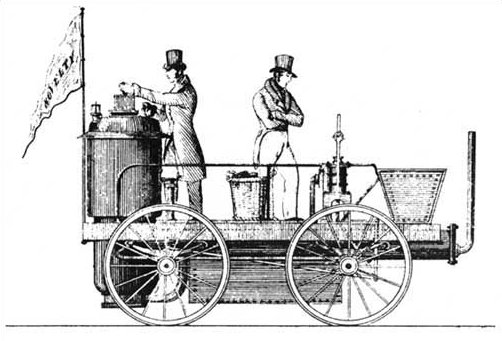

Ericsson and Braithwaite’s Novelty

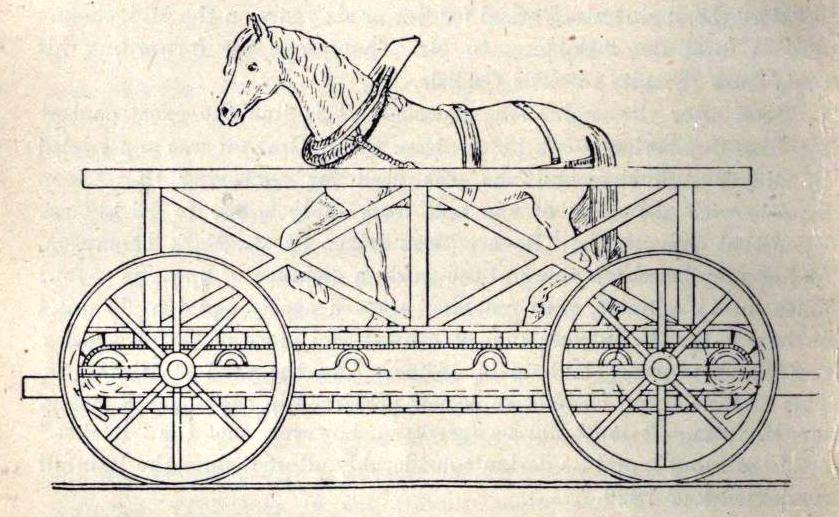

Another entrant Cycloped was disqualified as instead of steam the locomotive was powered by a horse on a treadmill, it could not reach the required speed and was further hampered when the horse broke through the floor of the vehicle.

Perseverance was damaged in transit to the trials and it would take until the final day of the contest to get her running.

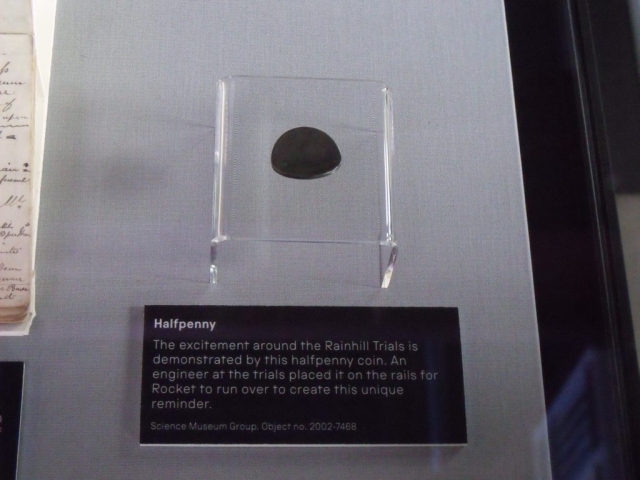

People came from far and wide to see the trials, many thousands of people lined the route and stands were erected for the viewing public.

Rocket though not the first listed for the test was the first locomotive ready and was paraded up and down the track for 12 miles without interruption in around 53 minutes.

Novelty was next called out it was a compact engine weighing just over three tons and was peculiar for the bellows that forced air through the firebox. The exhibited engine at times reached twenty-four miles per hour.

Mr. Timothy Hackworth’s Sans Pareil was the last to be exhibited that day, the engine was similar to the locomotive George Stephenson had constructed for the Stockton and Darlington Railway where Mr. Hackworth worked as a foreman.

The following day both Novelty and Sans Pareil suffered mechanical failures and the contest was postponed until the following day. To entertain the disappointed crowds Rocket was hitched to a coach containing 30 people and ran along the route attaining speeds of twenty to thirty miles per hour.

At 8am on the 8th October Rocket was brought out in order to take the test under the prescribed conditions. The fire-box was ignited and the required pressure was reached within an hour. The engine then started its journey and pulling 13 tons in waggons completed the required distance. The maximum speed was measured at twenty-nine miles per hour, almost three times the required speed, and the average over the whole of the journeys was fifteen miles per hour.

It wasn’t until the 10th that Novelty was fit for the trial. Only around seven tons was coupled up to the locomotive and the vehicle passed the first post in good style but on the return journey the pipe from the forcing-pump burst and brought an end to the trial.

It was the 13th before Sans Pareil was able to run, but on being filled with water it was found to be over the allowed weight. The judges, however, allowed the engine to run so they could consider whether it had any merits which would entitle it to favourable consideration. It started well, achieving an average speed of fourteen miles per hour, but on the eighth trip the cold-water pump failed, and the locomotive was unable to continue.

By this time Perseverance had finally been revived from the damage sustained on the way to Rainhill and it was decided that the following day would see the conclusion of the trials.

The owners of Novelty petitioned for another chance at the trial, but once again the locomotive broke down and it was eliminated from the competition. A request was also made for another chance for Sans Pareil, but this was refused due to the weight issue and also because the design of the blastpipe expelled large amounts of coke out of the chimney unburnt leading to it requiring about 692 lbs per hour to run.

Perseverence was found to be unable to reach more than six miles an hour and so was withdrawn before the required distance was covered leaving Rocket as the only Locomotive to complete the trial and the victor.

The original Stephenson’s Rocket is on display at Manchester Museum of Science and Industry until April 2019