The Lincoln Imp

In medieval times it is claimed that the Devil sent a plague of imps to the northern part of the country to cause mischief.

Those imps came first to St. Mary’s church in Chesterfield and amused themselves by twisting the spire.

The imps spread out around the area causing diverse mishaps and irritations.

It was not long before two of them arrived at Lincoln Cathedral, at that time the tallest building in the world.

The imps set about wreaking havock, smashing stained glass windows, knocking the bishop to the floor, blowing out all the candles and upsetting the tables and chairs.

Summoned by the infernal noise, an angel appeared from a bible that had been left open and chastised the imps. One hid in the detritus caused by their vandalism, but the other enboldened imp started throwing stones at its adversary from it’s perch high up in the Angel Choir.

Finally weary of the onslaught, “Wicked Imp, be turned to stone!” proclaimed the angel.

The wizened creature can be seen in his final position to this day.

Of the imp who hid, it is said he escaped and continued to cause mischief around the country until he was finally cornered by the angel in St James’ Church, Grimsby.

The angel soundly thrashed the imp before turning him to stone which is why he can be found clutching his bottom.

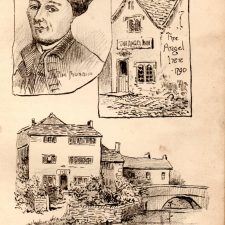

A Short History Of Tim Bobbin Lancashire Author, Poet & Artist

Self portrait of John Collier (Tim Bobbin)

As a Mancuniun, I came to Rochdale some thirty odd years ago, knowing nothing of this northern textile town. Coming from the big city I inevitably felt I was moving into the back of beyond, until my wife took me in charge and began my re-education.

She began by taking me to the parish churchyard to see the grave of Tim Bobbin’.

“Tim who?” I said.

“You’ll see!” said she, and we did.

As we stood there in the sunshine at the eastern end of the lovely grey church, beside the great slab of granite lying on top of poor Tim and his wife, I peered through the wrought iron railings protecting the grave from vandals to read the epitaph reputed to have been written by the incumbent just twenty minutes before his decease and decided that I had to find out more.

” Here lies John and with him Mary,

Cheek by jowl and never vary,

No wonder they so well agree,

John wants no punch, and Moll no tea.”

The Eleanor Crosses

When you see road signs telling you the distance to London the distance given is to a point at the South of Trafalgar Square where a statue to Charles I currently stands. A plaque on the floor tells you that this was the location of the original Charing Cross (a replica of which now stands outside Charing Cross Station.

To find out how the original hamlet of Charing came to get such a monument and the addition to it’s name, we have to go back to the end of the 13th Century.

Three Rush-Bearings (1906)

We heard about it first in Ambleside. We were in lodgings half-way up the hill that leads to the serene, forsaken Church of St. Anne. It was there that Faber, fresh from Oxford, had been curate, silently thinking the thoughts that were to send him into the Roman communion, and his young ghost, with the bowed head and the troubled eyes, was one of the friends we had made in the few rainy days of our sojourn. Another was Jock, a magnificent old collie, who accepted homage as his royal due, and would press his great head against the knee of the alien with confident expectation of a caress, lifting in recognition a long, comprehending look of amber eyes. Another friend—though our relations were sometimes strained—was Toby, a piebald pony of piquant disposition. He allowed us to sit in his pony-cart at picturesque spots and read the Lake Poets to him, and to tug him up the hills by his bridle, which he had expert ways of rubbing off, to the joy of passing coach-loads, when our attention was diverted to the landscape. Another was our kindly landlady. She came in with hot tea that Saturday afternoon to cheer up the adventurous member of the party, who had just returned half drowned from a long drive on coachtop for the sake of scenery absolutely blotted out by the downpour. There the “trippers” had sat for hours, huddled under trickling umbrellas, while the conscientious coachman put them off every now and then to clamber down wet banks and gaze at waterfalls, or halted for the due five minutes at a point where nothing was perceptible but the grey slant of the rain to assure them—and the spattered red guidebook confirmed his statement—that this was “the finest view in Westmoreland.” So when our landlady began to tell us of the ancient ceremony which the village was to observe that afternoon, the bedrenched one, hugging the bright dot of a fire, grimly implied that the customs and traditions of this sieve-skied island—in five weeks we had had only two rainless days—were nothing to her; but the tea, that moral beverage which enables the English to bear with their climate, wrought its usual reformation. Read more »

The Doctor and the Devil

LONGDENDALE has always been noted for the number of its inhabitants devoted to the study of magic arts. Once upon a time, or to give it in the words of an unpublished rhyme (which are quite as indefinite)—

LONGDENDALE has always been noted for the number of its inhabitants devoted to the study of magic arts. Once upon a time, or to give it in the words of an unpublished rhyme (which are quite as indefinite)—

“Long years ago, so runs the tale,

A doctor dwelt in Longdendale;”

and then the rhyme goes on to describe the hero of the legend—

“Well versed in mystic lore was he—

A conjuror of high degree;

He read the stars that deck the sky,

And told their rede of mystery.”

Coming down to ordinary prose, it will suffice to say that the doctor referred to was a most devoted student of magic, or, as he preferred to put it—“a keen searcher after knowledge”—a local Dr. Faustus in fact. Having tried every ordinary means of increasing his power over his fellow mortals, he finally decided to seek aid of the powers of darkness, and one day he entered into a compact with no less a personage than His Imperial Majesty, Satan, otherwise known as the Devil. The essentials of this agreement may thus be described.

Mead and the Honeymoon

In ancient times honey was revered for its healing properties. It was the only natural sweetener readily available and has the distinction of being the only foodstuff that doesn’t go off.

This was also a time when water wasn’t necessarily safe to drink due water borne diseases and parasites, so the sterilising properties of alcohol made weak beers and wines the drink of choice.

Although often referred to as “honey wine” true mead is brewed from honey, water and yeast without other ingredients such as grapes or other fruits. (The earliest recorded recipe for mead dates to 60AD)

The combination of the safe to drink alcohol and the healing properties of the honey lead to mead being revered (especially since it was often brewed by druids, and later, monks)

As part of the wedding ceremony, the bride’s father was expected to provide the newly wed couple with enough mead to last the couple for the first month of their marriage, hence the term Honeymoon, and this was said to encourage fertility and vitality (rather than brewer’s droop) and ensure that the marriage would “bear fruit” and a child would be born within a year.

Congratulations to Lee and Jennifer (9th September 2016)

Kanu y Med (Song of Mead)

I WILL adore the Ruler, chief of every place,

Him, that supports the heaven: Lord of everything.

Him, that made the water for every one good,

Him, that made every gift, and prospers it.

May Maelgwn of Mona be affected with mead, and affect us,

From the foaming mead-horns, with the choicest pure liquor,

Which the bees collect, and do not enjoy.

Mead distilled sparkling, its praise is everywhere.

The multitude of creatures which the earth nourishes,

God made for man to enrich him.

Some fierce, some mute, he enjoys them.

Some wild, some tame, the Lord makes them.

Their coverings become clothing.

For food, for drink, till doom they will continue.

I will implore the Ruler, sovereign of the country of peace,

To liberate Elphin from banishment.

The man who gave me wine and ale and mead.

And the great princely steeds, beautiful their appearance,

May he yet give me bounty to the end.

By the will of God, he will give in honour,

Five five-hundred festivals in the way of peace.

Elphinian knight of mead, late be thy time of rest.

From the Book of Taliesin XIX

Tree Lore – Blackthorn

The Blackthorn, which is widespread and abundant in woods and hedgerows throughout the British Isles, has the most sinister reputation within Celtic folklore, in ancient Ireland it was known as Straif, thought to be the origin of the word strife.

Although associated with trouble and bad luck, it is also associated with the overcoming of these negative aspects and the transformation that this struggle can bring.

Cailleach the Celtic goddess of winter is depicted as a blue veiled old woman with a raven on one shoulder and a blackthorn staff which she uses to summon storms. She emerges at Samain and takes over the year from the summer goddess Brigid.

The Giant of Sessay

The Darrel family owned Sessay (a small Yorkshire village around 4 miles from Thirsk) from the end of the 12th century to the days of Henry VII. It was during reign of that king, that the three sons of George Darrel died without fathering heirs, the manor therefore passed to his daughter — a strong-minded young woman, named Joan.

Taking advantage of the lack of a lord to defend the manor an evil giant took up residence in the woods around the village. He was a huge brute in human form — legs like elephants’ legs, arms of a corresponding size, a face most fierce to look upon, with only one eye, placed in the midst of his forehead; and a mouth large as a lion’s, garnished with teeth as long as the prongs of a pitchfork.

His only clothing was rudely fashioned from cow hides; while over his shoulder he carried a stout young tree, torn up by the roots, as a club.

Bowd Slasher

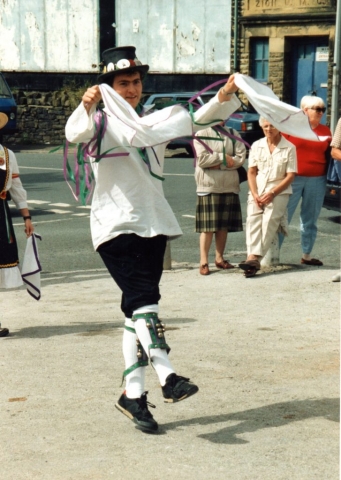

For hundreds of years the Peace Egg or Pace Egg play was a common part of the Easter festivities in Lancashire with bands of disguised mummers going from house to house presenting their play.

Gradually what was once an adult tradition became one enacted by children often gaining more in donations than their parents could earn in the wool and cotton industries.

Below is an contemporary observation of one of these performances by the Lancashire dialect writer John Trafford Clegg (Th’ Owd Weighver)