A Short History Of Tim Bobbin Lancashire Author, Poet & Artist

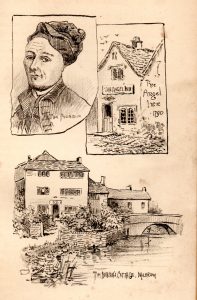

Self portrait of John Collier (Tim Bobbin)

As a Mancuniun, I came to Rochdale some thirty odd years ago, knowing nothing of this northern textile town. Coming from the big city I inevitably felt I was moving into the back of beyond, until my wife took me in charge and began my re-education.

She began by taking me to the parish churchyard to see the grave of Tim Bobbin’.

“Tim who?” I said.

“You’ll see!” said she, and we did.

As we stood there in the sunshine at the eastern end of the lovely grey church, beside the great slab of granite lying on top of poor Tim and his wife, I peered through the wrought iron railings protecting the grave from vandals to read the epitaph reputed to have been written by the incumbent just twenty minutes before his decease and decided that I had to find out more.

” Here lies John and with him Mary,

Cheek by jowl and never vary,

No wonder they so well agree,

John wants no punch, and Moll no tea.”

According to an entry in the family bible, in the beautiful hand of John Collier (Tim Bobbin) himself, he was born 16th December 1708, although the date of his baptism in the church records of the parish church at Flixton, is seen to be 6th January 1710, which is rather a long period of time to have elapsed between birth and baptism for those days when it was more usual to have a child baptised at the first possible opportunity due to the high rate of child mortality. He was born at a house known as as Richard o’ Jones in Flixton

His father, also called John, was born in 1682 of a family of small landholders who settled at Newton in Mottram, Cheshire. He was minister at Stretford in 1706, and in 1709 styled curate of Eccles. In 1716 he was “admitted to perform the office of Deacon at Hollinfare (Hol1ins Green). He was also the schoolmaster at Flixton and as such was responsible for the education of his own children.

Young John, the future Tim Bobbin, was considered by his father to have superior intellect, and was accordingly educated by him with a view to following his father into the ministry. This however was not to be as his father in his forty sixth year was deprived of his sight: this was a blow to young John now in his fourteenth year, for it meant the interruption of his education and he was required to make some contribution to the family finances. His parents decided that he should be apprenticed to a dutch loom weaver of Newton Moor in the parish of Mottram, a trade to which he seems to have had an aversion, since he only served his master for the period of little more than a year before he managed to persuade him to cancel his indentures. It is a mute point as to whether his master was swayed by

his rhetoric or by his own dissatisfaction with his idle and disinterested apprentice.

Now in his sixteenth year and free to follow his own inclination he became an itinerant schoolmaster, which whilst not being a lucrative profession seems to have quite suited his easy going temperament. In this fashion he spent the next five or six years, instructing a variety of students in the three ‘Rs’ – reading, writing and arithmetic. During this time he was employed in a variety of places,

Middleton, Bury, 0ldham and Rochdale, and in the villages between, until nearing the age of twenty-one he became engaged as an usher to Mr Pearson, Curate and schoolmaster of the free school at Milnrow. The school had been built by Mr Townley of Belfield Hall near Milnrow who also nominated the schoolmaster at a salary of twenty pounds a year which in this instance was shared by the curate with his assistant. Colonel Townley son of Mr Townley became the patron of Tim Bobbin during his lifetime, and his biographer after death. With the remuneration he received from the curate and fees from a night school, our hero was quite content, not being himself anxious for riches, nor for high office, for the love of money does not appear among his vices. A man with a most pleasant disposition and an entertaining conversational manner, he soon became a favourite companion of other like minded persons in the Milnrow neighbourhood.

A few years after John Collier’s appointment Mr Pearson died, and such was the popularity of his young assistant that he was offered the position of schoolmaster at the Milnrow Free School. He was well thought of in the village and his appointment was greeted with great enthusiasm, and with a stipend of £20 a year he was considered to be a young man of consequence.

In his spare time young John amused himself taking lessons in drawing and learning to play the English flute and the hautboy or oboe, becoming sufficiently skilled in these accomplishments to be well qualified in the instruction of others. As an artist he became skilled in landscape painting and produced many tasteful pictures of the locality. As a portrait painter he was not so proficient. He also

developed a skill in drawing caricatures which brought him some fame and notoriety locally. He also began to write poetry at this time having previously written nothing more than a few satires on local worthies and eccentrics; possessing an ascerbic wit, like Robert Burns, he would lampoon well known local characters, particularly any who might offend him, but as there was no one else in the area considered capable of such pieces he invariably bore the blame as the author.

He became quite the country beau and was looked up to and imitated by the local farmers’ sons, both in dress and manner as seen by the occasion one Sunday morning at church, when one of the local young ladies accidentally lost her imitation pearl necklace and John jocularly on finding it, wore it round his own throat for a laugh. As the congregation hurried into chapel he forgot he was

wearing it and caused some merriment inside as people noticed his unusual adornment. Realising the amusement at his expense to make the best of it and continued to wear the necklace for some time after the service, the upshot of this episode was that several of the young bloods of the neighbourhood took to imitating him and were to be seen wearing similar ornaments. Such behaviour may seem strange to our more sophisticated minds but one must remember that in the eighteenth century the population was less educated than now and there was a shortage of amusement for the majority of the population who could not even read or write.

In 1740 John Collier published a satirical verse entitled “The Blackbird” which his patron Mr Townley observed “contained some spirited ridicule on a well known Lancashire Justice of the Peace more renowned for his political zeal and ill timed loyalty than good sense and discretion. It was however, hardly a poetic. success being mere doggerel, but it served to enhance his reputation.

In penmanship, however, he excelled, writing in a fine strong hand, and carrying on a steady correspondence throughout his life with friends and relations and this along with his duties as schoolmaster, his skill as a musician, and the convivial hours he spent with his cronies in the local inns, ensured that his ten years as a bachelor at Milnrow were perhaps the happiest of his days. His life

however, complete as it was, he felt lacking in companionship of a wife. On realising this he set about correcting the omission, soon finding the answer to his problem in Miss Mary Clay of Flockton.

Mary was the daughter of Mr clay of Flockton in the parish of Thornhill near Huddersfield, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, where she was born. She was raised at Sedgham, at the residence of Lady Betty Hastings, and  lived in London for a number with her aunt Mrs Pitt, a woman of property married to an officer in the Tower of London. She was on a visit to another aunt, Mrs Butterworth

lived in London for a number with her aunt Mrs Pitt, a woman of property married to an officer in the Tower of London. She was on a visit to another aunt, Mrs Butterworth

of Milnrow, when our John first saw her and became enamoured with this young and pretty London lady who seemed to possess all the graces. The young lady must have reciprocated his feelings for they were married on the first of April 1744, at Helmsley, when the bride’s aunt, Mrs Pitt provided her with a dowry of three hundred pounds and several silk gowns and various articles of elegant clothing. Poor John however it seems, was so overcome by his good fortune that he soon dissipated his wife’s fortune by indulging in “large potations” of alcohol at which time he became sober and settled down to a more settled married life, his wife being heard to comment that she was happy when the money was spent. Two years later, in August 1746, the river Beal broke its banks at Milnrow and their cottage, which stood probably at the lowest point in Milnrow was flooded to a depth of four feet in the parlour, ruining all of Mrs Collier’s silk dresses.

The union with his wife proving fruitful, John was obliged to apply himself to providing sustenance for his family and so putting aside his musical instruments and satirist’s pencil he took up the brush and pallet to supplement his income. Although he could never have claimed fame as a skilled artist, he nevertheless produced altar pieces for country churches and chapels which were accepted

as fine pictures by those who engaged his services. He was also occasionally employed in the production of inn signs, an activity it is said, more congenial to our hero than the decoration of the house of god. How good an artist he was we are unable judge as none of his artisitic productions seems to have survived.

Whilst such employment must obviously have broght some relief to the demands of his household expenses, John found that he still had to look further afield for relief, and in a facetious moment he hit upon the idea of painting in caricature much in the style of the English artist Hogarth. This form of illustration proved to be successful beyond his wildest expectations; with bold strokes of genius he portrayed the drunkard, the bully and the clown in all their excesses and extravagances to the merriment of all who beheld them. They became very popular being bought with enthusiasm by the wealthier members of the society in which he lived and worked that he had to increase his production.

His skill increased with his industry and he was soon able to paint a single portrait in the hours that he had to spare after a day’s teaching; a group of three or four figures might take him a week. On completing a picture John would take on the role of salesman and take the picture to one of Rochdale’s principal inns to be sold, where, as they proved to be so successful, the inn keeper was more than usually willing to participate, and for a consideration would play the part

of agent. Naturally, Mr Collier being a congenial sort of person would on the completion of a sale show his grateful appreciation by spending a great part of what he had earned in the said inn, and so by frequent visits to the tavern he became familiar with the habit of imbibing the delights dispensed by his agent. Gregarious by nature, possessed of a convivial nature and an amusing conversationalist, John Collier was much sought after by his fellow drinkers, whose admiration and adulation he enjoyed. Meanwhile the popularity of his paintings increased throughout the district and his fame spread to Rochdale and Littelborough, Manchester and even far off Liverpool, from which city large orders were received from that town’s merchants for exportation to the Americas. As a result of the increasing interest in his art, the painter found himself “wishing for two pairs of hands” to cope with the demand particularly from abroad. Unfortunately our hero now had the reputation of a wit and a humourist, he was known as a boon companion and was in great demand at every festive occasion, and being of a free and generous disposition found the money he earned so easily was spent just as easily.

Although his time and attention was taken up by schoolmastering and painting, and despite his debauchery, John Collier still harboured a desire to produce something of a literary nature that might survive its author. This was a work of a local nature which became his famed ‘View of the Lancashire Dialect’, containing the “Adventures and Misfortunes of a Lancashire Clown”, by Tim Bobbin, in which he published items in the Lancashire dialect, mainly of the Rochdale and Milnrow area, and other parts of Lancashire that he had visited.

The first edition of the work proved very popular in the northern parts of the country and was soon sold out so that it became necessary to arrange a second impression in order to satisfy the public interest. Indeed the work was so successful that other unscrupulous booksellers were encouraged to print and circulate spurious works of the Lancashire dialect which led our author to believe “that there was not an honest printer in Lancashire”. To circumvent a repetition of this in a third edition of the work, he introduced illustrations of his own weird and original designs, and added a glossary of words and phrases in the Lancashire dialect.

Tim Bobbin, as our hero was now known, in this way reached the height of his reputation in the year 1750 whilst still in the prime of life and at the peak of his intellectual powers. Well known as an artist, successful as an author, considered by his neighbours and friends to be a person of high intellect with a propensity for fun, he was often visited by persons of rank for his wit and conversation. He spent many happy hours at the inn where amongst his admirers and acquaintances was a wealthy cloth manufacturer and merchant from Kebroyd near Halifax, who so delighted in his company that he offered him the position of clerk in his counting house promising him a very high salary along with a comfortable house for his family. No doubt he relished the thought of the pleasure and amusement to be had by the constant presence of his talented employee, in addition to the advantage he would derive from his skill in arithmetic and the beauty of his handwriting. The offer appeared to Tim to be so irresistible that he entered into an agreement binding himself to service for ten years: but tempting as the offer was, he must have had some doubts at the back of his mind for when it came time for him to inform his patron, Richard Townley esquire of Belfield, and tender his resignation from the position of schoolmaster of Milnrow, he begged him not to be too hasty in filling the seat he was vacating as he had some forebodings that he would not enjoy his new situation even though it seemed so advantageous to both himself and his family for whose sake he had in fact been induced to make this move. Mr Townley readily agreed to his request whilst hoping at the same time that Tim would be able to reconcile himself to his changed circumstances, but his presentiment proved correct, and both the new master and servant soon came to realise that companionship in the ale house and the absolute authority Tim exercised over his students in no way prepared him for the new relationship. Tim found that the application required for posting accounts in a ledger too constricting to one of his temperament, and the taking of instruction from his new employer irksome, nor could he ‘take to the mode of transacting business in Yorkshire’, so that on a visit to his old patron

at Belfield, just two months after taking up his new, position, Tim admitted he was unhappy and again begged Mr Townley not to fill his old position…

It seems that Mr Hill soon became aware of the situation and being an honest man suggested to his disgruntled clerk that if he disliked his employment he would be prepared to release him from his articles at the end of the first twelve months. This news was joy to Tom’s ears and he immediately wrote to Mr Townley to ensure himself of the position he most desired. In the meantime Mr Hill’s father had been making objections about the extravagant salary being

paid to the new clerk and it was mutually agreed by all parties that the agreement should be cancelled forthwith, and on the evening of the day of his release Tim hired a cart to take his family and his household effects back over Blackstone Edge to Milnrow, and by six o’ clock the following morning they were back in their old cottage feeling that they had never been away. Tim was so overjoyed at his release that he wrote the following letter to a friend:-

Dear frd Dan,

I felt several strong notions in the inward man, that prompted me to write to you about the time I commenced a Yorkshire man but one ill contrived thing or another, kept my pen and paper at a distance. But now thank Jupiter, and my friends, I’m upon the eve of being John, Duke of Milnrow again: for my rib with my bag and baggage, are gone over the hills into merry Lancashire again, and twelve team of devils shall not bring me hither again, if it be in the power of Timothy to stop them. I intend to follow in a few days, and now having that old son of a whore, old Time by the forelock, I’ll stick to the flying rascal till I finish this epistle…

According to the account of Mr Townley, Tim came back across Blackstone Edge, that grim barrier between Lancashire and Yorkshire full of joy and happiness, and reveling in his re-found freedom. He wasted no time in going to Belfield to see his benefactor to discover if he might re-commence his profession of schoolmaster and on being assured that the situation was his for the asking, he declared his

intention never again to desert the village of Milnrow. When Tim returned to Milnrow he had a wife, three sons and a daughter to support, and it was plain his return to more humble circumstances meant that he would have to work all the harder in his spare time, with his pen, his brush and easel to supplement his income; this he freely acknowledged and was soon working at a pace that had the inns of Rochdale and Littleborough brimming with examples of his artistic

ability, their walls adorned with his caricatures of grinning old men and mumbling old women on broomsticks.

He was a faithful and loving husband and father, whose wish was to preserve his family and provide for them to the best of his ability. He was also a constant

friend and jovial companion, with a keen eye which he employed to interpret the life around him with his pencil and his brush, even though apparently he some times overstepped the bounds of modesty in some of his paintings and engravings for illustrations of what he was pleased to call “The Human Passions”. Unfortunately, examples of his art do not seem to have survived to the present day

After his return from bondage as he liked to call it – in Yorkshire, Tim lived a contentedly quiet 1ife in the village of Milnrow enjoying the esteem of his friends and neighbours, who in turn enjoyed his ingenuity, his wit, and his sketching. In addition to his painting and drawing he began to employ his spare moments in

composing poetry and became a regular correspondent with his many friends and acquaintances, employing a fine elegant hand and a penetrating, if acid, wit. He delighted in the name of Tim Bobbin by which he had become known from the sale of his earlier work, the famed “View of the Lancashire Dialect”; he was an industrious worker in all the things he undertook and by his efforts as an artist, poet and writer was able to supplement his stipend as a schooimaster sufficently to support his growing family, not only with the plain necessities of life, but also with some of the luxuries also.

Tim had six children, three sons and three daughters. John the eldest was a house painter by trade and worked for many years in Newcastle after serving his apprenticeship, where, having been judicious in the care of his money, he felt himself affluent enough to enter into the ‘holy state of marriage’. He built himself a house, but having encroached upon a turnpike road found himself embroiled in litigation which quite turned his mind, and he and his wife had to return to his native Milnrow, where his neighbours undestanding his affliction treated him with tolerance and kindness. He and his wife earned a living by hand loom weaving. Like his father, this John was skilful with the drawing pencil also and amused the children of the village by sketching their likenesses in chalk, a medium unfortunately not given to preservation.

Tim’s second son was also a house painter who after wandering far and wide returned to his native heath to end his days where he lived to a good old age.

The third son, Thomas, was like his father, a schoolmaster, and exercised his profession in Packer Street near the site of the future town hall. Whether he was successful in tending the minds of his young charges it is impossible to say as nobody seems to have left any testimonial to him.

We know even less about the three daughters of Tim and wife Mary than we do about their sons. One of them Betty, is said to have married a dyer and earned her livelihood as a mid-wife, in which office she was reputed to be very accomplished. Another of the daughters married a sea captain and left her native, village to return no more, and of the third and last daughter we find no

mention at all in the records I have seen.

In 1773, in the spring of the year, Tim went to Liverpool where he held an exhibition of his paintings, which proved to be very successful, all exhibits being disposed of at a handsome profit to the Liverpool merchants who still saw in them a good investment and sent many of them abroad to the West Indies in the expectation of making a profitable return.

Tim returned home to Milnrow where he continued to be friend and companion to all and sundry, the life and soul of many a merry evening, despite the onset of old age and infirmity. Towards the end of his days he had the great satisfaction of seeing his favourite work, “A View of the Lancashire Dialect” go into a fifth edition. He appears to have spent the remainder of his life in serenity and to have died at his loved village on the 14th day of July, 1786, in his 78th year, surviving his wife by a few weeks only and being laid to rest beside her in the peace of Rochdale Parish Churchyard.

As an author and a poet John Collier rarely rose above the mediocre, but in an age when the common labourer was uneducated he shone 1ike a beacon brightening the drab lives of those around him and leaving a legacy by which he is still revered by many at the present day.

Gordon Batty, 1997

The Works of Tim Bobbin Editor John Corry 1862.

0ld & New Rochdale & It’s People: Wm Robertson 1881.

Social & Political History of Rochdale : Roberston 1889

Rochdale & the Vale of Whitworth: Wm Robertson 1897.

Davenport’s Illustrated Guide to Hollingworth Lake 1986 (Facsimile of the 1872 edition)

Beyond the Fringe: Harvey Kershaw 1970

Hi I am decedent over John Collier,and I share some of his Traits!!

A fantastic read,thank you very much.

I am also a descendant and am his 6th ggd and can relate to this as well. I am an artist, too, and an active professional creative. Funniest part and most surprising to me—is as a 10 yr old I would illustrate poems that my girlfriends and I would write at school being silly and I would draw caricatures with grotesque features. I wasn’t serious about it all at that age but just drew all of the time. And later in college I did receive acknowledgment from our National President of the schools that I might should consider doing caricatures—which shocked me as I never considered that as a job. (I went on into fine art and graphic design though.)

I am descended through his son Charles who died in Milnrow on 10 Sep 1815, and his son, Robert. Robert died in 1860 in South Carolina, USA.

I truly appreciate finding this very informative and entertaining read about John Collier/Tim Bobbin. Thank you! – Paige