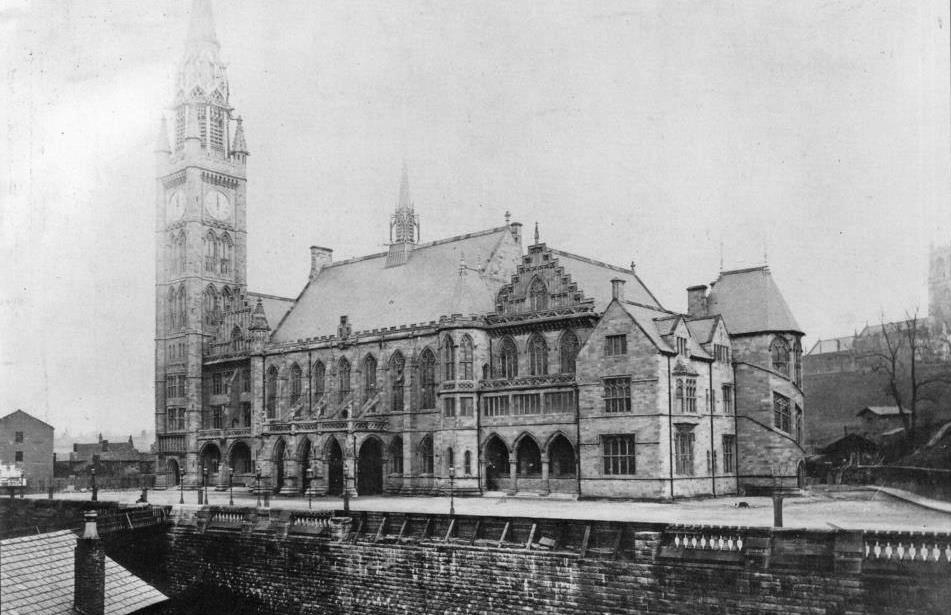

Gordon Batty Collection – Parish Church of St. Chad, Rochdale.

There is a tradition that the Parish Church of Rochdale was intended to have been erected down by the river, but that when the foundations were being laid, overnight they mysteriously disappeared, to re-appear at the top of the hill near the present site of the church. Several attempts were made to build in the valley, but each time the same thing occurred, and the materials would mysteriously be moved over-night, so eventually it was agreed to build the church on its present site, and no further trouble was experienced. This in not an unfamiliar tale and St. Chad’s is not the only church to which it has been ascribed.

The church was built and consecrated in 1170 and restored and enlarged in 1857 and 1885

Up to 1635 the floor of the church was hard packed earth, kept warm in winter by the rushes that were strewn on the floor. These rushes were gathered ceremoniously in August every year and borne on a cart in procession, accompanied by musicians, morris dancers, and the congregation to the Parish Church where they were laid on the floor with ceremony. On occasions, hedgehogs were released among the rushes in an effort to keep down the pests and vermin. Sometime after 1635 the church floor was paved with stone, but nevertheless, the Rushbearing Ceremony continued into the twentieth century when it lapsed for some years before being revived in August 1986.

In 1552, a two manual organ was installed in the church, one of only four such organs found in churches at that time in the country; the others being in Manchester, Ormskirk and Middleton.

A west gallery was erected in 1693, to be followed in 1669 by the erection of the south gallery, but both of these were removed during a period of alterations in 1885.

The belfrey in 1719 contained five bells, which were increased to six in June 1751, and another bell was added in 1787 taking the number to eight. In 1812 a new tenor bell was struck.

The church bells played an important part in teh life of the people of Rochdale for many centuries, ringing out the curfew at eight O’clock every evening. The curfew bell was rung in every parish church by the Royal Command of William I – The Conquerer – the reason being that in his day, and for many centuries after, buildings consisted of wood and thatched roofs, and as such were dangerously liable to catch fire, so the king ordered that all churches should ring the curfew bell an hour before sunset to warn the population that it was time to damp down their fires for the night. Originally the bell was called the ‘covre feu’ (Cover fire) but with time became corrupted to curfew. In time it became less essential to ring out this warning but it had become such a tradition that it was continued throughout the centuries.

For many years a bell was rung at 5:45am on workdays to remind working people of the need to rise and prepare for the day’s labour, so that no-one could make the excuse that they were unaware of the time because they could not afford a watch or clock.

For many years a public clock existed in the church tower, this can be seen in the many old prints that still exist of it, and in 1788, a local man, John Barnish, was commissionesd to make a new clock to replace the one that had worn out, for which service he was paid the sum of £350. This clock chimed a tune on the hour, playing a different tune for each day of the week. These tunes were, starting with Sunday:-

- he Old 104th Psalm Tune

- Lovely Nancy

- Life Let Us Cherish

- Ipswich

- Port Patrick

- The Old 103rd Psalm Tune

- Britons Strike Home

In 1872 the clock dials were removed and used to face the clock mounted in Dearnley Workhouse – which later became Birch Hill Hospital – where they can still be seen at the present time.

The Rectory

The present building was erected in 1752, the Vicar at the time was Dr. Dunster, and was designed on the lines of a Georgean house in Red Lion Square in London, prior to this time the Rectory was an ancient thatched building.

In the Rectory garden there is reputed to be a section of Anglo-Saxon stone wall which is thought to be the remains of an earlier church, built by one of St. Augustine’s missionaries, and which stood on the site before the present church.

In the early nineteenth century the living of the Rochdale Church was one of the richest in the country, much of the wealth coming from the nearby Glebe Lands which in 1783 covered one hundred and thirty acres, and which included Broadfield Park.